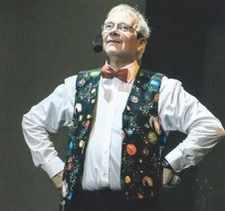

The Anglo-Saxon period is often known as the Dark Ages because of the lack of information we have about this period of time, but astronomically it could not be more interesting. In this lively and fast-moving Zoom lecture from a flamboyantly attired Martin Lunn, he demonstrated that by CE 900 there were diverse views about the heavens in Britain, with Celtic, Roman/Greek, Saxon and Viking influences all competing and mixing with each other.

Whilst today our framework of astronomy uses Babylonian and Greek foundations, in Britain in the period from two to three thousand years ago, Neolithic and Celtic mythology and traditions bound the night sky to events, symbols and culture. It is important to appreciate that the Sun, the Planets, the Moon and the Constellations appeared much the same to these early peoples as they do today. For instance, the Celts recognised the Constellation “Hu Gadarn”, a combination of modern Auriga, Ursa Major and Bootes. In their mythology Hu Gardarn was the first person to link oxen to a plough, from which it is easy to understand why in Britain we call those seven stars of Ursa Major “The Plough”. They called Orion “Mabon”, the only god who could handle the hunting dog “Drudwyn” (Sirius).

Things became more complex when the Romans arrived in BCE 54. Though they had gods, goddesses and mythology galore, they had little astronomy of their own. Instead they had Greek astronomy (in turn borrowed from the Babylonians). And, accordingly, the two strands of astronomy ran in parallel with constellations such as Cepheus, Cassiopeia, Andromeda and Perseus being recognised. The Romans also brought equipment with them – a water clock and a candle clock – breaking down a day into 24 hours as invented by the Babylonians over 4000 years earlier. Martin reminded us that the Romans build Watling Street running from Kent to Shropshire; interestingly the Celts referred to the Milky Way as “Waetling Street”.

After the Romans left in 410 CE, then came the Saxons and a further layer of astronomy and mythology was added. Saxons called The Plough “Irmines Wagen” (a wagon!), and the Pole Star “Scip Steorra” (the Ship Star). A 6th Century monk, St Gildas, was a prominent figure during this period and wrote about a period of darkness that occurred between CE 534 – 548. It corresponds to a time when tree ring growth stopped and it may be that this describe a Tunguska event that was reported elsewhere. Another significant character of this period was the Venerable Bede, one of the greatest scholars of the Anglo-Saxon period. He noted the relationship between Tides and the phases of the Moon.

As if three strands of mythology and astronomy weren’t enough for the people of Britain, then came the Vikings who stayed here from 793 – 1066. They too brought their traditions with them. At that time 32 Camelopardalis was the Pole Star, so the Earth’s precession was understood. The Vikings saw Orion as a female character, the goddess Frigg, who was a spinner (does this suggests maybe the Vikings could see the Orion Nebula as a naked eye object?).

The Anglo Saxon chronicles describe a number of astronomical events – eight solar eclipses, eleven lunar eclipses, ten comets, two meteor showers; the Bayeux tapestry shows Halley’s Comet. On the face of it this suggests that these early Britons were well aware of matters astronomical. Yet there are notable omissions – the Supernova of 1054 (widely reported by Chinese and Korean observers) that gave rise to M1, the Crab Nebula, is mentioned nowhere. So, these peoples’ knowledge was extensive but incomplete and stemmed from multiple influences over many centuries. As Martin concluded, now that we look more closely at this type of work, take away the florid, imaginative language, then this can nevertheless lead us to an understanding of real astronomical events.

Sandy Giles

Commentaires